Press-room / news / Science news /

On Selectivity of K+-channels: How Do Proteins Know About the Square Antiprism?

Potassium channels are one of the major players in the transduction of the nerve impulse, and mutations in their genes lead to neurological and cardiovascular diseases. The most important feature of K+-channels is their highest selectivity for K+ over Na+ and other cations. In the new work, members of the Group of in silico Analysis of Membrane Proteins Structure and the Laboratory of Molecular Instruments for Neurobiology analyzed all known 3D-structures of membrane proteins. As a result, the key principle of K+-channel selectivity filter architecture was confirmed: within it, oxygen atoms of the protein backbone are arranged in a chain of square antiprisms, replicating exactly the solvation geometry of the potassium ion. Distortion of the filter, for example during inactivation, is detected by the algorithm developed by the authors, which can be used for structural classification.

The first spatial structure of a K+-channel, the bacterial protein KcsA, was solved by researchers led by Roderick McKinnon in 1998, for which he later won a Nobel Prize. They also determined that the selectivity filter (SF), a conserved structure in the channel pore responsible for selective passage of only potassium ions, with a remarkable precision reproduces the structure of the hydrated K+ ion: each of the four SF sites capable of binding potassium (S1–S4) is formed by eight oxygen atoms in a square antiprism geometry, ensuring that the ion is conducted in its desolvated form without an energy penalty. Since then, structural biology has moved a long way forward, and today >350 structures of different K+-channels are available. We asked the following questions: “Is the mechanism of selectivity the same in all potassium channels?” and “Is the selectivity filter unique to K+-channels, or can it be found in other proteins?”

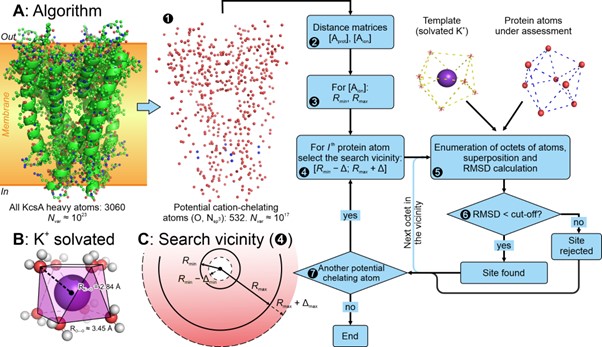

Different metal cations are hydrated (“dressed” by water molecules) in different ways: they have different coordination numbers, solvation geometry, and characteristic distances from the ion to the surrounding H2O molecules. K+ is “dressed” with eight water molecules organized into a square antiprism, a shape resembling a twisted cube (Fig. 1B). It is the antiprism that became the template for our algorithm to search for K+-binding sites in protein structures (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Algorithm to reveal K+-binding sites in protein structures. Potentially ion-chelating protein atoms are divided into local octets (the algorithm scheme is presented in panel A), which are compared to the template (shown in panel B). In the case of a good match (RMSD < 1.25 Å), the octet is treated as a K+-binding site and stored for further analysis.

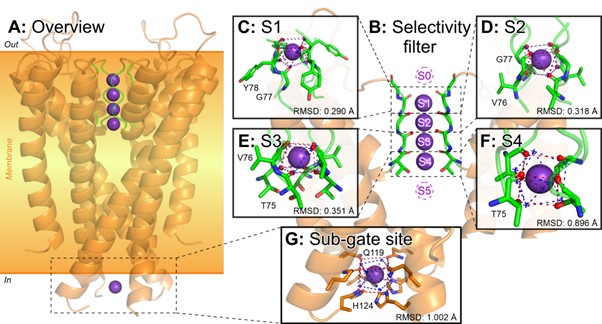

The algorithm reveals S1–S4 sites unmistakably in the SF structures of K+-channels annotated as active (Fig. 2). Apparently, it is the four coaxial sites that provide high selectivity for potassium; no such structures were found in any other proteins. Something similar to the classical SF was found in related K+-transporting proteins, but due to distinct structure, no more than two sites were located, leading to a selectivity drop.

Figure 2. K+-Binding sites in potassium channels clearly specify the selectivity filter. The algorithm unmistakably finds coaxial quads of such sites in the structures of active potassium channels, which is the basis for selective ion conductance. Interestingly, some K+-channels (and other proteins) contain binding sites outside the SF (panel G), but they never line up to form an SF-like architecture.

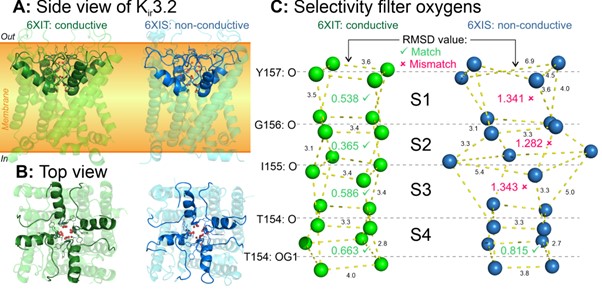

Interestingly, the algorithm did not find exactly four sites in all K+-channel SF structures (Fig. 3). In some cases, there were none, or just one or two sites were found. It turned out that such structures correspond to inactivated states of the channel, whose SF is distorted and cannot conduct ions, or to mutant forms with a loss of K+-selectivity. Our algorithm reliably registers such cases.

Figure 3. Distortion of the K+-channel selectivity filter is the mechanism of C-type inactivation. A first glance at the “normal” and inactivated structures is unlikely to distinguish between them (panels A and B). However, our algorithm reveals a key difference: in structures captured in the inactivated state, the SF is significantly distorted, which breaks the K+-binding sites (panel C).

In addition to all available K+-channel structures, we analyzed all known structures of other membrane proteins (>7000) and a fraction of non-membrane proteins (≈10 000). We showed that the number of K+-binding sites in those proteins is dramatically smaller, and nowhere do they line up in SF-like structures. However, such sites were identified in K+-transporting proteins (NaK, CNG, and HCN channels, as well as Na+/K+-ATPases), providing them with ion binding functionality.

Answering the question posed in the title of this release, it is clear that the square antiprism formed by chelating atoms in proteins is a key motif in the coordination of potassium ions.

The work is published in the International Journal of Biological Macromolecules and is available free of charge until April 10th, 2025.

february 24